Compiled for the Center for Adaptive Stress as a work in progress, please send message to admin for updates and corrections.

*This paper was developed as part of an ongoing two-year collaboration between myself and the AI research assistant ChatGPT, whose contributions span drafting, refinement, conceptual alignment, and literature integration. While I (Lori Hogenkamp) remain the sole human author and originator of the Evolutionary Stress Framework (ESF), this work reflects the iterative dialogue and synthesis made possible through advanced AI co-writing.

Together, we’ve worked not only to articulate the limitations of genetic determinism in neurodiversity research, but to build a scientifically grounded, systems-level alternative grounded in emergence, energy regulation, and allostatic adaptation. Throughout this process, I have used AI not as a replacement for human insight but as a powerful tool to accelerate clarity, coherence, and interdisciplinary connection across stress science, neurodevelopment, complexity theory, and public health.

This project is a testament to the potential of AI-assisted inquiry when shaped by human vision, lived experience, and a commitment to truth-seeking. I am grateful for the growing possibilities this kind of hybrid research model represents

I. Introduction

The debate over what causes autism remains locked in a counterproductive binary: either genetic essentialism, which frames autism as a hardwired biological flaw, or environmental blame models, which reduce the condition to toxic exposures or parenting errors. Both positions oversimplify a highly dynamic and emergent developmental process. Despite over two decades of large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS), no singular genetic etiology has been found to account for autism’s heterogeneity. Common variants only explain a fraction of the variance (Grove et al., 2019), and even rare de novo mutations, such as those in SHANK3 or 16p11.2, show highly variable penetrance and phenotypic outcomes (Bertero et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2022).

At the same time, environmental models have often drifted toward linear cause-effect thinking, promoting the idea that specific toxins (e.g., heavy metals, pesticides) or maternal behaviors directly “cause” autism. While many of these factors are real and influential, the reductionist search for a single cause ignores the emergent, systems-based nature of neurodevelopment. Stress exposure, endocrine disruption, and immune activation influence autism risk not through deterministic pathways, but via complex feedback loops, developmental timing effects, and nonlinear thresholds (Dietert et al., 2011; Gee & Casey, 2015; Ellis & Del Giudice, 2019).

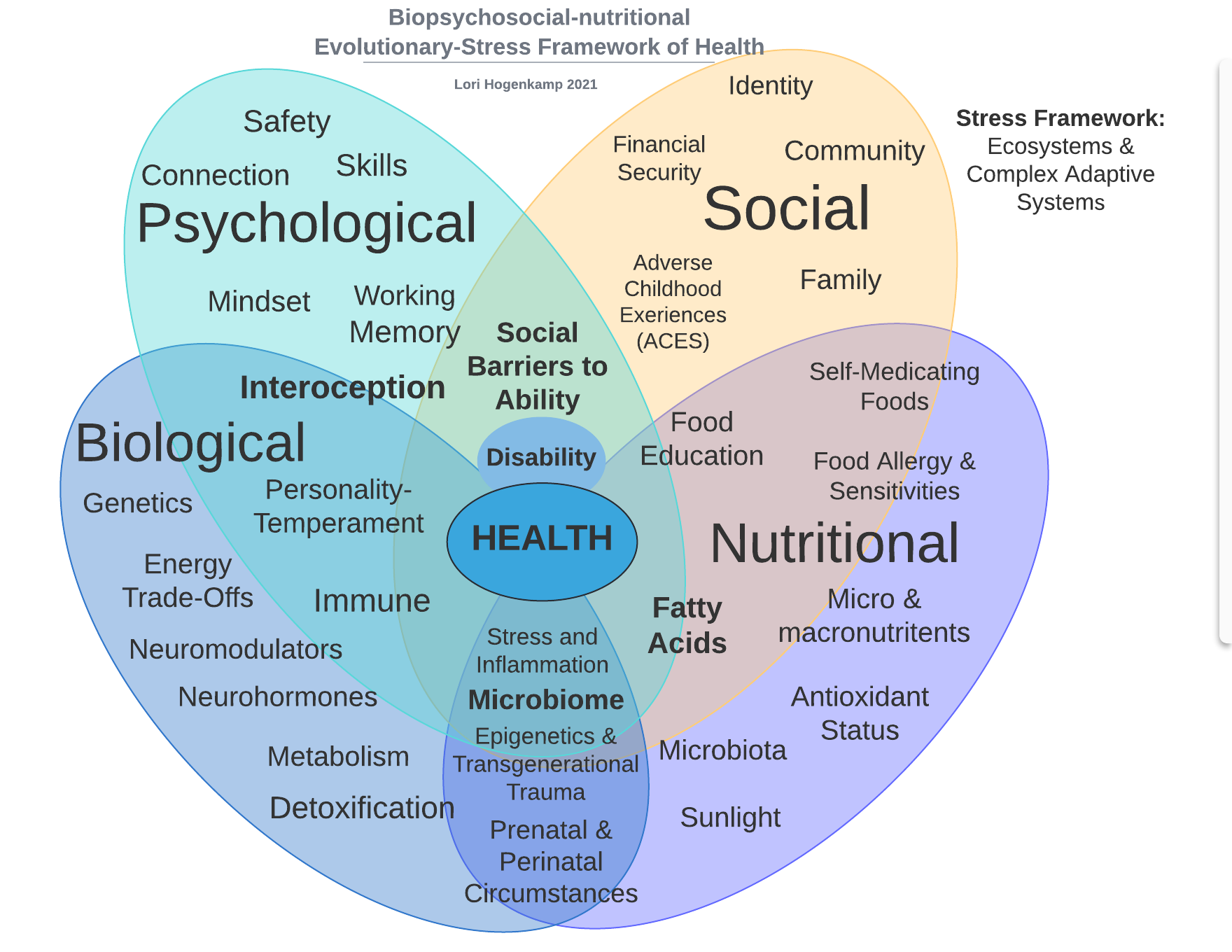

To move beyond these unproductive debates, this paper introduces two integrated, complexity-informed frameworks: the Biopsychosocial-Nutritional (BPSN) model and the Evolutionary Stress Framework (ESF). The BPSN model extends traditional biopsychosocial approaches by explicitly incorporating nutritional and metabolic scaffolding, emphasizing how energetic availability and biochemical inputs shape brain development and stress responsivity (Picard et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2019). The ESF builds upon this model by situating autism not as a disorder to be cured, but as a developmentally emergent neurotype—a phenotype shaped by the interaction of biological starting points (bio-neurotypes), stress leverage points, and ecological context.

Together, these frameworks challenge the logic of linear causation and instead reframe autism as a complex, adaptive calibration process driven by prediction, energy regulation, and system-wide coherence.

II. The Biopsychosocial-Nutritional Model

The biopsychosocial model, introduced by George Engel in 1977, was a groundbreaking attempt to move beyond reductionist biomedical frameworks by integrating psychological and social dimensions into health care (Engel, 1977). However, despite its wide adoption in theory, its implementation has been limited, often relegated to surface-level psychosocial add-ons rather than deep structural integration. Furthermore, it lacks a critical element essential to neurodevelopmental conditions like autism: nutrition and metabolic scaffolding.

To address this, we propose the Biopsychosocial-Nutritional (BPSN) model, a systems-level framework that integrates energy regulation, nutrient availability, and gut-brain-immune interactions into the existing biopsychosocial paradigm. This integration is especially urgent in light of autism’s known associations with mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, immune dysregulation, and gut microbiome alterations—factors that are not adequately captured by genetic or behavioral models alone (Frye et al., 2013; Gialloreti et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020).

A. Subsystem I: Biological Foundations

The biological domain includes genetics, neuroendocrine development, immune tone, and allostatic regulation. Autism is characterized by both increased genetic heterogeneity and heightened stress responsivity, often shaped by sex-differentiated pathways and prenatal immune activation (Warrier et al., 2022; Moison et al., 2021; Beversdorf et al., 2020). These biological substrates define bio-neurotypes—innate starting points in stress, salience, and energy systems—that are modulated by environment and experience.

B. Subsystem II: Psychological Processing

The psychological dimension includes perception, prediction, and interoception—the brain’s internal model of the body. Autistic individuals often display spiky interoceptive profiles, either hyper- or hypo-attuned to bodily signals, impacting emotion regulation and prediction accuracy (Barrett, 2017; Russell et al., 2019). These are not merely cognitive traits, but metabolic processes reflecting the energetic cost of regulating attention, emotion, and sensory salience.

C. Subsystem III: Social Relationality

The social domain includes attachment systems, stress buffering through relationships, and cultural scaffolding. Early life stressors such as attachment disruptions or socio-environmental instability can significantly recalibrate stress pathways, with effects mediated through the HPA axis, oxytocin signaling, and immune function (Gee & Casey, 2015; Ellis & Del Giudice, 2019). Rather than labeling these responses as “maladaptive,” the BPSN model frames them as context-sensitive calibrations to environmental uncertainty.

D. Subsystem IV: Nutritional and Metabolic Inputs

The nutritional domain includes the gut microbiome, micronutrient sufficiency, fatty acid composition, and mitochondrial function. Nutrition is not simply a background variable; it is the energetic substrate upon which all other domains depend. For instance:

- Omega-3 fatty acids improve cognition and reduce inflammatory signaling (Huang et al., 2020; Esposito et al., 2021)

- Gut microbiota influence neurotransmitter synthesis and immune modulation (Kang et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019)

- Vitamin D and sunlight regulate neuroimmune tone and antioxidant protection during development (Jia et al., 2015; Yin et al., 2018)

- Mitochondrial dysfunction is prevalent in autistic individuals and contributes to energy inefficiency (Frye et al., 2013; Picard et al., 2018)

Rather than treating these as comorbidities, the BPSN model frames them as core scaffolding variables influencing how the brain develops and adapts to stress.

Why Nutrition Must Be Centered

While psychosocial models recognize experience-dependent plasticity, they rarely ask: what is the system adapting with? Metabolic capacity determines whether prediction errors can be updated, whether inflammation can be cleared, and whether sensory inputs can be buffered. Autism may therefore emerge when a bio-neurotype with high energetic demand is exposed to chronic stress without adequate nutritional or relational buffering.

“Energy is the currency of life. Allostasis is the cost. Autism may represent a high-cost strategy under low-buffering conditions.”

— Evolutionary Stress Framework (in development)

III. Autism as an Emergent Neurotype

Rather than a fixed disorder caused by singular genetic mutations or environmental insults, autism is increasingly understood as a developmentally emergent neurotype—a nonlinear outcome that arises from the dynamic interplay of biological predispositions, environmental constraints, and energetic scaffolding over time. In this view, causation is not linear but recursive, with early influences shaping the system’s regulatory logic, which in turn modifies its developmental trajectory.

A. Bio-Neurotypes as Initial Conditions

At the foundation of emergence are bio-neurotypes: innate physiological and neurocognitive profiles shaped by genetics, prenatal epigenetic programming, neurohormonal calibration, and early immune tone. These profiles set the initial conditions from which developmental adaptation unfolds. Bio-neurotypes are not disorders in themselves but trait-based energetic configurations—each with strengths, vulnerabilities, and differential thresholds for stress and stimulation (Del Giudice, 2018; Moison et al., 2021).

These bio-neurotypes align with evolutionary models of brain-behavior systems proposed by Fisher (2009), who identified distinct neurochemical temperaments—such as dopamine-driven novelty-seekers and serotonin-based cautious systems—suggesting that neurodiverse traits represent evolved cognitive strategies, not dysfunctions.

For example, autistic profiles may emerge from:

- Heightened systemizing bias and pattern salience (Crespi, 2016)

- Reduced oxytocin receptor expression or altered vasopressin pathways (Baribeau & Anagnostou, 2015)

- Imbalanced excitatory-inhibitory signaling in glutamate-GABA systems (Bourgeron, 2015)

- Elevated sensory gain and interoceptive amplification, leading to high environmental sensitivity (Markram et al., 2010; Russell et al., 2019)

These bio-neurotypes reflect evolutionarily conserved strategies for processing information and managing uncertainty—often adaptive in specific ecological contexts but vulnerable in environments with chronic mismatch or insufficient scaffolding.

B. Stress Leverage Points and Developmental Calibration

Development does not proceed in a vacuum. Instead, stress leverage points—key windows during which the system is particularly plastic and susceptible to reorganization—modulate how bio-neurotypes express across time. The timing, intensity, and context of these stressors (e.g., prenatal inflammation, caregiving unpredictability, sensory overload) can either reinforce coherence or push the system toward dysregulation (Gee & Casey, 2015; Ellis & Del Giudice, 2019; Beversdorf et al., 2021).

This aligns with dynamical systems theory, where early perturbations can tip developing systems into distinct attractor states—stable patterns of organization that resist change and shape future responses (Davila-Velderrain & Alvarez-Buylla, n.d.).

“Phenotypes like autism reflect not damaged outcomes, but attractor trajectories reached through high-sensitivity adaptations to energetic and informational contexts.”

— Evolutionary Stress Framework (in development)

Importantly, stress here is not inherently “toxic.” It is the medium through which adaptation occurs—a signal that drives predictive recalibration across neurodevelopmental subsystems (Barrett, 2017; Picard et al., 2018). When buffering is adequate (e.g., through stable attachment, optimal nutrition, or circadian entrainment), stress facilitates resilience and specialization. When buffering is insufficient or unpredictable, the system may amplify defenses, leading to more rigid or fragmented outcomes.

C. Emergent Neurotypes and Multifinality

Autism, therefore, does not emerge from a single trajectory, but from multiple, converging developmental routes—a concept known as multifinality. Different bio-neurotypes can yield similar outward profiles (e.g., social withdrawal, repetitive behavior), while similar genetic or environmental inputs can result in divergent outcomes depending on when and how they interact (Johnson et al., 2021; Warrier et al., 2022).

This explains the heterogeneity within autism and its frequent comorbidities with other high-sensitivity profiles like ADHD, anxiety, or chronic pain. These comorbidities are not additive disorders, but overlapping expressions of a system under energetic and regulatory strain (Bölte et al., 2019; Masini et al., 2020).

Understanding autism as an emergent neurotype thus redirects inquiry away from “what caused it?” and toward more generative questions:

- How was the system organized to manage complexity, uncertainty, and energy?

- What are the trade-offs and adaptations embedded in this neurotype?

- How can environments be structured to support coherence rather than correction?

IV. Genetic and Environmental Interactions: From Causation to Calibration

The traditional medical framework treats genetics and environment as separate, competing explanations for autism. On one side are genetic determinists, who point to hundreds of identified common and rare variants. On the other are environmental attribution models, which implicate endocrine-disrupting chemicals, prenatal inflammation, and maternal stress. However, this opposition conceals a deeper truth: genetic and environmental influences do not act independently—they are interdependent components of a regulatory system shaped by stress, energy, and time.

A. Genes as Sensitivity Parameters, Not Determinants

Large-scale genetic studies have confirmed that no single gene or mutation accounts for autism. Rather, the genetic architecture is polygenic, pleiotropic, and probabilistic (Grove et al., 2019; Warrier et al., 2022). Genes act more like sensitivity thresholds—calibrating a system’s responsivity to environmental signals and stress input (Thomas et al., 2022; Clarke et al., 2015).

Research shows that many autism-linked genes are synaptic, metabolic, or transcriptional regulators, and their expression is highly plastic—modulated by early experience, inflammation, and nutrient status (Masini et al., 2020; Bertero et al., 2018). In this view, genetic variation creates diverse bio-neurotypes, which then adapt to the quality of stress exposure and buffering environments they encounter.

“Genetic vulnerability is not a sentence—it’s a set of coordinates in a regulatory space that interacts with everything from micronutrient availability to maternal immune tone.”

— Evolutionary Stress Framework (in development)

B. Epigenetics as the Bridge

Epigenetics serves as the communication language between genes and environment, particularly via DNA methylation, histone modifications, and miRNA signaling (Choi & Friso, 2016; Rassoulzadegan et al., 2021). These mechanisms translate environmental cues—such as stress, infection, or nutrient deprivation—into long-lasting changes in gene expression that shape developmental outcomes.

For example:

- Prenatal stress and maternal immune activation are associated with increased autism risk via cytokine signaling and HPA-axis programming (Beversdorf et al., 2021; Zerbo et al., 2014).

- Micronutrient deficiencies (e.g., folate, vitamin D, zinc) alter epigenetic profiles of key developmental genes (Li et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020).

- Microbiome composition influences neurodevelopment through epigenetically active metabolites like butyrate and serotonin precursors (Kang et al., 2019; Abdellatif et al., 2020).

These findings underscore the inadequacy of cause-effect models. Autism does not result from genes or environment alone but from recursive loops where early signals get locked in and elaborated over time (Davila-Velderrain & Alvarez-Buylla, n.d.).

C. Developmental Timing and Nonlinear Amplification

The effects of both genes and environment are non-monotonic and timing-dependent—a small perturbation at a sensitive period may amplify across developmental stages (Gee & Casey, 2015; Johnson et al., 2021). For instance, exposure to immune stressors during the second trimester may recalibrate microglial development and alter synaptic pruning, even if genetic risk is low (Gąssowska-Dobrowolska et al., 2020; Masini et al., 2020).

This aligns with nonlinear dose-response theories, such as those describing endocrine disruptors and mitochondrial dysfunction—where low-level exposures at key periods can produce high-magnitude effects (Miodovnik et al., 2011; Gyllenhammer et al., 2020). These relationships cannot be captured by linear risk models.

D. A New Logic: Interdependence Over Opposition

Under the BPSN and ESF frameworks, we reject the false opposition of “nature vs. nurture” and replace it with a logic of interdependence:

- Genetics creates diversity in bio-neurotype sensitivities.

- Environment provides the context in which those sensitivities are expressed.

- Stress is the mediator that translates experience into biology.

- Energy and timing determine whether that translation results in coherence or dysregulation.

V. The Central Role of Energy and Coherence

All biological systems are constrained by energy. From mitochondrial ATP production to neural signaling and immune regulation, energy is the substrate of adaptation. Yet most models of autism—and health more broadly—fail to account for how energy regulation governs development, stress responsivity, and the emergence of neurotypes. The Evolutionary Stress Framework (ESF) and the Biopsychosocial-Nutritional (BPSN) model reposition energy not as a side variable but as the organizing force in neurodevelopment, with coherence and entropy as key outcomes.

A. Health as Emergent Allostasis

In the ESF, health is not defined by the absence of disorder but by emergent allostasis: the system’s ability to regulate itself across domains—biological, psychological, social, and nutritional—in a way that maintains coherence despite internal and external stress. This goes beyond the homeostasis metaphor. Allostasis involves prediction, flexibility, and energetic budgeting—and it explains why some neurodivergent profiles thrive in certain environments but fragment in others (Sterling, 2012; Barrett, 2017).

“The definition of health must evolve from static equilibrium to dynamic coherence—what we call emergent allostasis.”

— Evolutionary Stress Framework

In autistic development, traits like sensory amplification, deep focus, or pattern recognition carry high energetic costs. When systems are unable to meet those costs due to inflammatory load, mitochondrial dysfunction, or social unpredictability, adaptive strategies become rigid or dysregulated (Picard et al., 2018; Frye et al., 2013).

B. Energetic Intelligence: The Hidden Substrate of Development

Energetic intelligence refers to the system’s ability to allocate energy adaptively: to sense internal need, respond to prediction errors, downregulate inflammation, and scaffold attention and emotion. This capacity is biologically embedded in systems like:

- The interoceptive network (insula, anterior cingulate cortex), which tracks bodily needs and cues (Barrett & Simmons, 2015)

- The HPA axis, which sets thresholds for safety, alertness, and recovery (Ellis & Del Giudice, 2019)

- Mitochondrial networks, which determine energy availability at the cellular level (Picard et al., 2018)

- The gut-brain axis, which modulates neuroinflammation, nutrient transport, and stress signaling (Kang et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020)

Autistic traits are often better understood as high-intensity energy allocation profiles: individuals may devote disproportionate energy to sensory processing, attention, or emotional calibration—leaving less reserve for social modulation, stress resilience, or immune regulation.

This explains both the “spiky profiles” of autistic individuals (Meilleur et al., 2015) and their vulnerability to energy collapse during prolonged stress (Gyllenhammer et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2019).

C. Entropy, Coherence, and the Cost of Prediction

Entropy in this framework refers to the degree of unpredictability or disorganization in a system. Autistic individuals often operate at the edge of high internal entropy—experiencing unpredictability in sensory input, interoception, and social signaling. This is not inherently pathological. In fact, high-entropy systems are often creative, precise, and adaptive—but they require more coherence scaffolding (Capra & Luisi, 2014; Fisher, 2009).

Coherence emerges when prediction and environment are aligned—when the internal model can efficiently anticipate sensory and social demands. If prediction errors mount (e.g., in socially chaotic or inflammatory contexts), the system may shift toward defense, rigidity, or shutdown. This is not maladaptive—it is a form of energetic conservation under duress (Barrett, 2017; Del Giudice, 2018).

“Autism is not a failure of development—it’s a calibration strategy in a system trying to maintain prediction under energy constraint.”

— Evolutionary Stress Framework

D. Energy as the Missing Link in Autism Research

Despite mounting evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction, altered glucose metabolism, and increased oxidative stress in autistic individuals (Frye et al., 2013; Manivasagam et al., 2020), energy remains under-discussed in both research and policy. The ESF argues that any meaningful shift in autism science must:

- Recognize autism as an adaptive neuro-energetic profile, not a broken system

- Shift the focus from fixing symptoms to building coherence

- Move away from causal blame toward systems-level support for regulation and prediction

This would reshape the narrative of autism from “risk” to adaptive trade-off, and allow for interventions focused on increasing energetic capacity, not suppressing traits and necessary energy and stress regulating strategies (ie stimming).

VI. Implications for Practice and Policy

Understanding autism through the lens of emergent neurotypes, energetic trade-offs, and systemic coherence has profound implications. It requires a shift away from interventions that attempt to normalize behavior or reduce “symptoms,” and toward ones that support the system’s capacity to regulate, predict, and stay energetically viable. This has relevance for early intervention, clinical care, educational practices, public health frameworks, and even the ethical structure of autism research itself.

A. From Early Intervention to Early Calibration

Under the BPSN and ESF models, early intervention must no longer aim to “correct” behavior but instead stabilize energetic systems, enhance relational predictability, and tailor scaffolding to each child’s bio-neurotype. This means prioritizing:

- Predictability and sensory safety in early environments (Baranek et al., 2014)

- Relational co-regulation through consistent and attuned caregiving (Gee & Casey, 2015)

- Nutritional support that targets mitochondrial health, inflammation, and micronutrient sufficiency (Frye et al., 2013; Jia et al., 2015)

- Cultural flexibility in how we define developmental success (O’Hagan & Hebron, 2017)

This framework also cautions against interventions that create high stress loads—such as intensive compliance training or rigid socialization programs—that may lead to learned camouflaging and later mental health collapse (Hull et al., 2017).

“Calibration is not about normalizing behavior—it’s about aligning internal and external rhythms so that regulation becomes possible.”

— Evolutionary Stress Framework

B. Redefining Support Through Coherence

Services and supports should focus less on skill-building in isolation and more on building coherence across systems. This involves:

- Matching environments to energetic profiles (e.g., reducing sensory load or pacing demands)

- Teaching interoceptive awareness and body-mapping skills (Mahler, 2021)

- Utilizing stress-reducing practices such as mindfulness, animal-assisted therapy, or nature-based regulation (Sharda et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2021)

- Creating community scaffolding where difference is expected and affirmed, not pathologized

Rather than emphasizing “resilience” as the ability to withstand stress, coherence-based supports emphasize energetic sustainability and the reduction of costly adaptation patterns such as shutdown, dissociation, or over-masking.

C. Policy: From Risk Management to System Design

In public health and education policy, autism is too often framed as a “risk factor” to be identified and managed. This framing leads to:

- Overemphasis on genetic screening without understanding context

- Environmental “toxin-chasing” that lacks complexity (e.g., vaccine blame narratives)

- Resource distribution skewed toward normalization, not ecosystem design

The ESF argues for a shift toward system design: investing in environments that support a wide range of neurotypes across development, particularly those with high entropy or energetic sensitivity. This could include:

- Built environments designed for sensory modulation

- Food and nutrition policies that prioritize neurodevelopmental needs

- Screening and assessment tools that identify regulatory patterns, not just behavioral deficits

- Anti-fragility metrics that reward developmental flexibility, not conformity (Crittenden & Claussen, 2000)

Such a shift also reframes disability itself—not as defect, but as evidence of system strain and as a signal that conditions are out of alignment with individual energy and regulation needs.

D. Research: Toward Complexity-Aware Methodologies

Scientific research must evolve beyond gold-standard, linear, single-variable designs that strip away the very systems we need to understand. Instead, autism research should prioritize:

- Longitudinal, multimodal, and recursive models of development

- Transdisciplinary teams that integrate neuroscience, immunology, nutrition, and trauma studies

- A shift from “cause-seeking” to leverage-point mapping, using dynamic systems and machine learning models

- Participatory methods that include autistic and neurodivergent co-researchers to ensure validity and ethical integrity (Pellicano & Stears, 2011)

“When we control for complexity, we lose the ability to see what actually matters.”

— Evolutionary Stress Framework

VII. Conclusion

The search for what “causes” autism has led us into a conceptual cul-de-sac: an unresolvable tug-of-war between genetic determinism and environmental blame. This paper has argued that to move forward, we must abandon the logic of linear causation and embrace a systems view that recognizes autism as an emergent neurotype—the product of adaptive calibration in response to biological, psychological, social, and nutritional conditions.

The Biopsychosocial-Nutritional (BPSN) model expands the classical biopsychosocial framework by integrating the role of energy, metabolism, and ecological scaffolding into neurodevelopment. The Evolutionary Stress Framework (ESF) complements this model by offering a theory of how stress mediates system regulation, leverage points, and emergent complexity. Together, these frameworks reframe autism not as a dysfunction but as an adaptive profile of regulation, perception, and energetic strategy.

We propose that future discourse on autism must:

- Replace single-cause explanations with models of multifinality and recursive adaptation

- Recognize bio-neurotypes as diverse and valid cognitive-energy architectures

- Redefine health as emergent coherence, not normalized behavior

- Invest in early calibration, coherence-based supports, and community design rather than symptom suppression

- Align research with complexity-informed, longitudinal, participatory, and transdisciplinary methods

This shift is not just scientific—it is ethical. To continue framing autistic people as broken or at risk is to misread the adaptive signals of a system responding to uncertainty, constraint, and complexity. In contrast, the BPSN and ESF frameworks allow us to move toward a future in which diverse neurotypes are understood, supported, and valued within their unique energetic and ecological contexts.

“Let us stop chasing symptoms, and start understanding systems.”

References: (*references are currently being double-check and a work in progress, please send message to admin for updates and corrections)

Abdellatif, A. M., et al. (2020). Gut microbiota and autism: Promising therapeutic targets. Nutrients, 12(8), 2383.

Baranek, G. T., et al. (2014). Sensory features in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(1), 1–12.

Baribeau, D. A., & Anagnostou, E. (2015). Oxytocin and vasopressin neuropeptides in autism spectrum disorders: A review of evidence for their role in social behavior. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 147. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00147

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Bertero, A., et al. (2018). Autism-associated 16p11.2 microdeletion impairs prefrontal functional connectivity in mouse and human. Brain, 141(7), 2055–2065. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awy111

Beversdorf, D. Q., et al. (2020). Prenatal stress and maternal immune dysregulation in autism. Neurobiology of Stress, 15, 100336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2021.100336

Bölte, S., Girdler, S., & Marschik, P. (2019). The contribution of environmental exposure to the etiology of autism spectrum disorder. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 76(7), 1275–1297.

Bourgeron, T. (2015). From the genetic architecture to synaptic plasticity in autism spectrum disorder. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(9), 551–563.

Choi, S. W., & Friso, S. (2016). Epigenetics: A new bridge between nutrition and health. Advances in Nutrition, 1(1), 8–16.

Clarke, T. K., et al. (2015). Common polygenic risk for ASD is associated with cognitive ability. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(3), 419–425.

Crespi, B. J. (2016). Autism as a disorder of high intelligence. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 10, 300.

Crittenden, P. M., & Claussen, A. H. (2000). The organization of attachment relationships: Maturation, culture, and context. Cambridge University Press.

Davila-Velderrain, J., & Alvarez-Buylla, E. R. (n.d.). The epigenetic attractors landscape. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Epigenetic-Attractors-Landscape-a-Through-a-dynamical-mapping-a-mathematical_fig3_261706702

Del Giudice, M. (2018). Evolutionary Psychopathology: A Unified Approach. Oxford University Press.

Dietert, R. R., Dietert, J. M., & DeWitt, J. C. (2011). Environmental risk factors for autism. Emerging Health Threats Journal, 4(1), 7111. https://doi.org/10.3402/ehtj.v4i0.7111

Ellis, B. J., & Del Giudice, M. (2019). Developmental adaptation to stress: An evolutionary perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 111–139.

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Esposito, S., et al. (2021). The role of omega-3 fatty acids in autism spectrum disorders. Nutrients, 13(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13010259

Frye, R. E., et al. (2013). Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Pediatric Biochemistry, 3(3), 185–193.

Gąssowska-Dobrowolska, M., et al. (2020). Prenatal exposure to valproic acid affects microglia and synaptic ultrastructure. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(10), 3576.

Gee, D. G., & Casey, B. J. (2015). The impact of developmental timing for stress and recovery. Neurobiology of Stress, 1, 184–194.

Gialloreti, L. E., et al. (2019). Risk factors associated with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3396.

Grove, J., et al. (2019). Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nature Genetics, 51(3), 431–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0344-8

Gyllenhammer, L. E., et al. (2020). Prenatal exposures and mitochondrial programming. Environmental Health Perspectives, 128(1), 017001.

Huang, T. L., et al. (2020). Omega-3 fatty acids and brain health. Brain Sciences, 10(9), 615.

Hull, L., et al. (2017). ‘Putting on My Best Normal’: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 2519–2534.

Jia, F., et al. (2015). Vitamin D supplementation improves symptoms in autistic children: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(6), 684–693.

Johnson, M. H., Charman, T., Pickles, A., & Jones, E. J. H. (2021). AMEND: A systems neuroscience approach to common developmental disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(5), 610–630.

Kang, D. W., et al. (2019). Microbiota transfer therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: An open-label study. Microbiome, 5(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0701-3

Li, Q., et al. (2020). Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of autism. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 14, 577030.

Mahler, K. (2021). Interoception: The Eighth Sensory System. AAPC Publishing.

Markram, H., Rinaldi, T., & Markram, K. (2010). The intense world theory – a unifying theory of the neurobiology of autism. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 224.

Masini, E., et al. (2020). Genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors in ASD. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(21), 8290.

Miodovnik, A., et al. (2011). Endocrine disruptors and childhood social impairment. Neurotoxicology, 32(2), 261–267.

Moison, D., et al. (2021). Sex-specific gene expression and susceptibility in autism. Nature Communications, 12(1), 6546.

O’Hagan, S., & Hebron, J. (2017). Perceptions of friendship among autistic girls. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 2, 2396941516682628.

Pellicano, E., & Stears, M. (2011). Bridging autism, science and society. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(10), 670–676.

Picard, M., et al. (2018). An energetic view of stress: Focus on mitochondria. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 49, 72–85.

Rassoulzadegan, M., & Grandjean, V. (2021). Epigenetics and RNA-mediated inheritance. Developmental Cell, 56(12), 1651–1663.

Russell, G., Mandy, W., & Ford, T. (2019). The diagnostic and social experiences of autistic girls and women: A qualitative study. Autism, 23(2), 328–341.

Sharda, M., et al. (2018). Music improves social communication and auditory–motor connectivity in children with autism. Translational Psychiatry, 8, 231.

Thomas, T. R., et al. (2022). Clinical autism subscales have common genetic liabilities that are heritable, pleiotropic, and generalizable to the general population. Translational Psychiatry, 12(1), 99.

Warrier, V., et al. (2022). Genetic correlates of phenotypic heterogeneity in autism. Nature Genetics, 54(9), 1293–1304.

Xu, M., et al. (2019). Altered gut microbiota and mucosal immunity in autism spectrum disorders. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 80, 572–582.

Yin, J., et al. (2018). Melatonin as a neuroprotective agent in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroscience Bulletin, 34(4), 451–457.

Zhao, M., et al. (2021). Animal-assisted intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 617925.

Leave a Reply